Artist Black and White Drawings

The greatest drawer in the world could have been a female apprentice to another artist in rococo France, or a Renaissance draftsman rendered invisible by the glare of an acknowledged master from a more powerful nearby city-state, or a self-effacing art instructor currently working in Minnesota. Choosing the top 10 drawers of all time is a parlor game of dubious value. Instead, we decided to tally the number of times historical figures were referenced or reproduced in the first 10 issues of Drawing magazine and showcase them with illuminating comments from a thoughtful working artist and a representative from one of the most respected art institutions in the country. Each of the 10 artists featured here offers drawings of exquisite beauty; but, more important to our purposes, each one offers insights and lessons any draftsman can use. We explore why the work of these individuals is so inspiring.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was art's first undeniable superstar, and his genius is indisputable. But Ephraim Rubenstein, an artist who teaches at the Art Students League of New York, in Manhattan, mixes his admiration for Leonardo with the point that even this Renaissance great did not emerge from a vacuum. "Leonardo got so much from Andrea del Verrocchio, who was a tremendous teacher," says Rubenstein. "Everyone comes out of a tradition; nobody comes from nowhere. Leonardo learned the beginnings of sfumato from [his teacher], among many other things." Born the illegitimate son of a lawyer in the Tuscan town of Vinci, Italy, Leonardo was a scientist, an inventor, a pioneer in the study of anatomy and the painter of the masterpieces The Last Supper and Mona Lisa—the prototypical Renaissance man. Rubenstein refers to his lines as "mellifluous, delicate and graceful. He doesn't do anything that doesn't have the most beautiful curves." But his sketchbooks are what make Leonardo an innovator. "He was one of the first guys who talked about taking a notebook out into the streets," explains Rubenstein. "Leonardo said you must have direct contact with life and observe men's actions."

Resources:

- Leonardo da Vinci Master Draftsman, by Carmen C. Bambach (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York)

- Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings, by Frank Zollner and Johannes Nathan (Taschen, Cologne, Germany)

Michelangelo Buonarotti

His Sistine Chapel ceiling is one of the most celebrated feats in art history, but those interested in drawings focus on the more than 90 chalk-and-ink works Michelangelo (1475–1564) made in preparation for this and other commissions. Some artists have drawn the parallel between this Italian master's work and the fantastical, muscle-bound forms in comic books. But if any aspiring draftsman over the last 50 years has approached the rippling human anatomy in comics with admiration, he has come to Michelangelo's work with awe. "With his mastery of painting, sculpture and the architectural, no artist—with the possible exception of Leonardo—was more technically gifted," says Rhoda Eitel-Porter, the head of the department of drawings at the Morgan Library, in New York City. "His figures are always exerting themselves," observes Rubenstein. "They are striving for something but are bound. All the muscles are tensed simultaneously, which is anatomically impossible, but deeply poetic. Michelangelo made a landscape of the human body." The reason is logical: Michelangelo was a sculptor. The separation between the tactile and the visual is broken down; the artist sees and draws in three dimensions. "Michelangelo [understood] that a particular muscle is egglike in character, and he [would go] after that shape with his chalk," says Rubenstein, pointing out that the marks on his drawings increasingly hone in on more finished areas of the form in a manner that parallels the chisel lines on an unfinished sculpture. The artist placed rough hatches in some places, more carefully defining crosshatching in others, and polished tone in the most finished areas. Michelangelo's work is marked by two other traits: his almost complete dedication to the male nude and the omnipresent sensuality in his art. Even female figures in his pieces were modeled after men, and even his drapery was sensual. "He could say everything he wanted to say with the male nude," notes Rubenstein. "He was not distracted by anything else—not landscapes, not still lifes, not female nudes. With the exception of his architecture, Michelangelo was monolithically focused on the male nude, and even in his buildings, parallels could be made to the body."

Resources:

- Michelangelo Drawings: Closer to the Master, by Hugo Chapman (Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut)

- Lessons From Michelangelo, by Michael Burban (Watson-Guptill Publications, New York, New York)

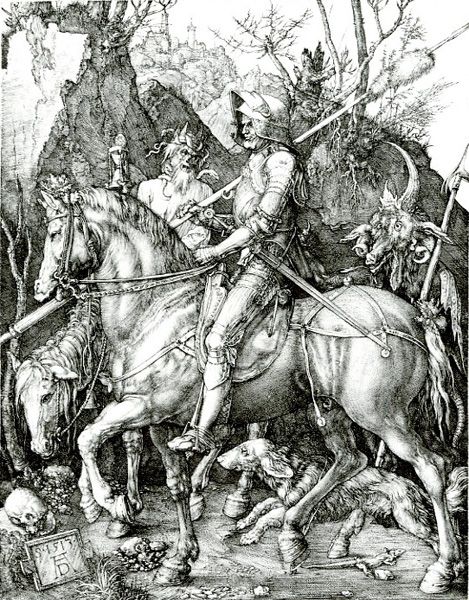

Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is arguably the greatest printmaker in history. He published more than 350 engravings and woodcuts and completed at least 35 oil paintings, generating more than 1,000 preliminary drawings and watercolors in the process. Dürer created a number of widely known and iconic prints, and the Nuremberg artist is highly respected and influential among drawers. His nuanced depiction of forms—no easy feat with a rigid, unforgiving engraving tool—is the reason so many draftsmen study and marvel at his work. "His drawing comes out of a printmaker's sensibility," comments Rubenstein. "He cannot lay down tone; he has to hatch. And nobody stays on the form with the ruthlessness of Dürer." He was virtuosic, but perhaps not innovative. "I think he received a lot from the Italians," says Rubenstein, in reference to the artist's visit to Venice to see a friend and investigate the art and ideas of Renaissance Italy. But his talent wasn't just in the execution of his technique. Dürer packed a lot of content in engravings such as Knight, Death, and Devil—including two phantasmagorical figures that fascinate yet don't dominate the rest of the composition—but the eye easily grasps the main idea when it isn't feasting on marvelously rendered roots and pebbles. Discover the power of sketching in our free e-book of Sketch Drawing Lessons. Just enter your email below to start enjoying drawing explorations of art masters like these! [fw-capture-inline campaign="RCLP-confirmation-pencil-sketch-drawing" thanks="Thanks for downloading!" interest="Art" offer="/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/PencilSketchDrawingGheno.pdf"] "You respond to the intensity and density of the image," states Rubenstein. "Dürer [depicted] the bizarreness of natural phenomena in great detail, yet he [was] able to keep the big composition clear and strong with all this going on. He [knew] that even within the gnarliness of the trees, he [had] to back off a little bit so the hourglass [could] come forward. He [controlled] so much—he's like a juggler that has 30 balls up in the air."

Resources:

- The Complete Engravings, Etchings, and Drypoints of Albrecht Dürer, by Albrecht Dürer (Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, New York)

- Albrecht Dürer and His Legacy: The Graphic Work of a Renaissance Artist, by Giulia Bartrum (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey)

Peter Paul Rubens

The stereotype has artists living a poor, Bohemian lifestyle, but Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) is evidence that some artists achieve immense success. By most accounts, Rubens was a well-respected, rich and happy artist who also collected antiques, raised a big family, and secured a peace treaty or two while serving as a high-level diplomat. He was a busy man of action, and paper was never doodled upon frivolously—nearly all of his drawings were preliminary studies for grander commissions. One marvels even more at the confident, beautiful lines of Rubens' drawings in light of the knowledge that he most assuredly would consider them working documents, unsuitable for exhibition. What makes him special is "his mastery of the chalk technique," according to Eitel-Porter. "He needed just a few strokes to evoke not only the figure's pose but also its emotional state." Indeed, the Belgian court painter demonstrated incredible facility in his drawings, with a hint of bombast. His hand was sure. "Rubens used naturally robust, confident marks and flowing gestures," says Rubenstein, who in particular admires the artist's drawings made with three colors of chalk. "Red chalk is beautiful, but it has a limitation on its range—you often want to use black chalk and white chalk to increase it further on each end of the value range," Rubenstein explains. "It's like the difference between a chord and one note—extending the reach of red chalk."

Resources:

- Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings, by Anne-Marie S. Logan (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York)

- Peter Paul Rubens: A Touch of Brilliance, by Mikhail Piotrovsky, (Prestel Publishing, Munich, Germany)

Rembrandt van Rijn

"He was an heir to Leonardo in that he was always sketching from nature," says Rubenstein in reference to Rembrandt (1606–1669). "His gestures were so true and full of life." If Rubens was the painter of power and the royal court, Rembrandt was the artist of humanity. Gifted with the same ability with line, the Dutch painter and draftsman had the skill to draw very quickly and to confidently add simple washes that efficiently established dark-light patterns. The unforgiving medium of ink was no hindrance to Rembrandt's pursuit of the moment's action; the back of his wife's robe sweeps convincingly off the stair in Woman Carrying a Child Down Stairs, for instance. Mothers and children were of special interest to the artist perhaps, in part, because he lost three children in their infancy; and his wife's death cut short a happy marriage. "The humanity of his drawings … you don't feel it so pervasively in the work of anybody else," remarks Rubenstein. "He [seemed] to know what the mother [felt] like, what the child [felt] like—what's going on in the scene. And he [had] a spontaneous, incredible line that could show the structure of something, and yet it [had] its own calligraphic sense."

Resources:

- Rembrandt's Journey: Painter, Draftsman, Etcher, by Clifford S. Ackley (MFA Publications, Boston, Massachusetts)

- The Drawings by Rembrandt and His School, Vol. I, by Jeroen Giltaij (Thames & Hudson, New York, New York)

- Drawings by Rembrandt and His School, Vol. II, by Jeroen Giltaij (Thames & Hudson, New York, New York)

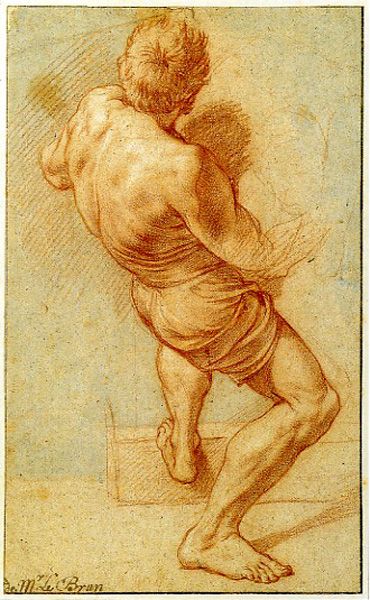

Charles Le Brun

With a foot in both the classical and the Baroque eras, Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) was an artist who found success early and had the political skills to remain a dominant figure in the French court and the Académie until very late in life. Le Brun was a student of Vouet and a friend of Poussin, and his compositions were built on basic, simple masses, as in classicism. And yet, his figures could bristle with the energy of Baroque art, as shown in the serpentine form in Study for Mucius Scaevola Before Porsenna.

Le Brun did more than anyone to establish a homogenous French style of art for three decades in the 17th century. He accomplished this through both policy and painting—Le Brun founded the French Academy in Rome and, by the 1660s, any significant commission was assumed his for the taking. The two drawings shown in this section ably illustrate how Le Brun's style pragmatically changed with the times—with both artistic and material success. "One image shows the simple conception of all the forms, very balanced and posed like a Raphael; and the other shows a figure struggling so hard," marvels Rubenstein. "Even without the indication of the corpse, which this figure is lifting, we feel how much effort he has to exert to hold up this heavyweight." Le Brun's surety with drawing instruments was legendary; one myth asserted that this son of a sculptor began drawing in the cradle.

Resources:

- Charles Le Brun: First Painter to King Louis XIV, by Michel Gareau (Harry N. Abrams, New York, New York)

- The Expression of the Passions: The Origin and Influence of Charles Le Brun`s Conference sur l'expression générale et particulière, by Jennifer Montagu, (Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut)

Edgar Degas

The transformation for a draftsman from drawing tight, detailed forms to looser, more gestural lines is a common one, but these examples show this evolution in Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) to be a particularly natural one. Beauty inhabits both works, even if a typical viewer may not associate both pieces with one artist. "He was trying to pin down the figure in his early drawings," explains Rubenstein, "and in the later drawings, he was setting it loose." Degas' muse was the ballerina, and the motion and movements of dance demanded free, gestural sketches. Rubenstein points out that even in quick sketches, such as Study of a Dancer in Tights, Degas is showing his genius for composition—the knees nearly touch the edges of the paper, and the negative shapes formed by the dancer's limbs create a powerful design. The beauty of the spontaneous composition betrays the years of experience behind this study.

Resources:

- Degas and the Dance, by Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall (Harry N. Abrams, New York, New York)

- Edgar Degas: Life and Work, by Denys Sutton (Rizzoli International Publications, New York, New York)

Vincent van Gogh

Aside from being the prototypical starving artist, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) was a midwife for the birth of abstract art, as evidenced in his Wild Vegetation. As a painter, he is renowned for his vibrant and bold color, but the risks he took with composition are perhaps equally responsible for his reputation. For drawers, van Gogh is also important for his mark-making. "Van Gogh developed an incredible vocabulary with the reed pen," says Rubenstein. "He [made] up a language, with all these different kinds of marks: dots, dashes, curls, long lines and short lines. But because he [was] in such control, it [made] sense. He [made] rhythms. Nature doesn't have these marks."

Comparing Pollard Birches to Wild Vegetation shows the Dutch artist's growth from representational to the almost completely abstract. The transition is on view to a lesser extent in the portrait The Zouave, in which the majority of the face is depicted with a kind of pointillism while specific features, such as the nose, are formed with classical lines. "It's a very personal language he [came] up with," comments Rubenstein. "But the marks themselves [are] mesmerizing."

:

- Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, by Colta Ives (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York)

- Van Gogh: Master Draughtsman,, by Sjraar van Heugten (Harry N. Abrams, New York, New York)

Egon Schiele

Austrian-born Egon Schiele (1890–1918) was a dandy cloaked in Bohemian clothes, a supposed pornographer, a determined narcissist and one of the most provocative and singular draftsmen of the modern age. "Compared to, say, Rembrandt, there's not a lot of range," says Rubenstein. "But you always know if something is a Schiele. How does this happen? That's worth thinking about." "All of his exaggerations are thoughtful," continues Rubenstein. "His distortions are on the money—the indentation of a hip, the swell of the haunch, a line that is clearly hamstrings. The distortions are based on very accurate anatomical landmarks. That's what makes them so disturbing. That, and the fact that the skeleton is often very present." Schiele was maligned for some of his explicit drawings of underaged girls, but the dismissal of all his erotic art may be a mistake. Rubenstein points out that not everyone can accomplish the erotic successfully. Schiele's art challenges through not only its subject matter but also in the positions of his subjects, the wandering lines that vibrate with tension and the boisterous colors he employed. "Look at the red next to the green running through the figure in Fighter," observes Rubenstein. "It speaks of something unspeakable." Eitel-Porter concurs, "His use of unnatural colors and his gestural application of paint, with visible strokes to emphasize expression, sets Schiele apart."

Resources:

- Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, by Jane Kallir (Harry N. Abrams, New York, New York)

- Egon Schiele: Drawings and Watercolors, by Jane Kallir (Thames & Hudson, New York, New York)

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) saw much suffering and depicted it with an empathy rarely rivaled. Her husband was a doctor for the poor in Berlin, which likely played a role in her socialist sympathies. Losing her son in World War I prompted a lengthy depression. She also lost a grandson in World War II. As a result, her heartbreaking images of mothers crying over deceased infants strike a resonating chord. "And she was such a great draftsman," says Rubenstein. "Kollwitz could do so much with simple shapes. Over here may be a few wispy marks signifying hair; and then—boom, you are riveted right into that eye with a few strong lines." Kollwitz was primarily a graphic artist, confining her work largely to black-and-white imagery. "Her bold, graphic style reflects the immense human pain and suffering of the underprivileged," comments Eitel-Porter. "That's the basis of her subject matter. The world she depicts is veiled in shadow; only rarely are touches of color introduced." Echoes Rubenstein, "With such simplicity, with such economy of means, she communicated great sympathy. She could make an incredible human statement with just burnt wood [charcoal] on paper."

Resources:

- Catalogue of the Complete Graphic Work of Käthe Kollwitz, by August Klipstein (Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, Delaware)

- Käthe Kollwitz Drawings, by Herbert Bittner (Thomas Yoseloff, New York, New York)

*Article contributions by Bob Bahr

***

For more drawing tips, instruction, expert insight and inspiration, check out past issues of Drawing magazine.

Artist Black and White Drawings

Source: https://www.artistsnetwork.com/art-history/masters-10-great-drawers-and-what-they-teach-us/

0 Response to "Artist Black and White Drawings"

Post a Comment